The Dean Recommends: Getting ‘Unhitched’ from the Old Testament? Andy Stanley Aims at Heresy

Eventually, we learn to take an individual at his word. Andy Stanley is a master communicator, and he communicates very well and very often. His preaching and teaching often bring controversy, and he quite regularly makes arguments that subvert the authority of Scripture and cast doubt upon biblical Christianity. He returns regularly to certain themes and arguments — so regularly that we certainly get the point. He evidently wants us to understand that he means what he says.

Earlier this year, Stanley brought controversy when he argued in a sermon that the Christian faith must be “unhitched” from the Old Testament. He claimed that “Peter, James, Paul elected to unhitch the Christian faith from their Jewish scriptures, and my friends, we must as well.”

Later, explaining his statement, Stanley told Relevant magazine, “Well, I never suggested we ‘unhitch’ from a passage of Scripture or a specific biblical imperative . . . . Again, I was preaching through Acts 15 where Peter, James, and Paul recommended the first-century church unhitch (my word, I’m open to an alternative) the law of Moses from the Gospel being preached to the Gentiles in Antioch.”

Indeed, in the sermon Stanley did not argue that any specific Old Testament command should be nullified. Instead, he went even further and told his listeners that the Old Testament should not be seen as “the go-to source regarding any behavior in the church.” In his view, the first century leadership of the church “unhitched the church from the worldview, value system, and regulations of the Jewish Scriptures.”

Again, controversy rightly erupted after those comments, spoken earlier this year. But in recent days Andy Stanley has returned to the same theme, this time in a conversation with Jonathan Merritt on his podcast, Seekers and Speakers.

In this conversation, Stanley speaks of outgrowing a childhood belief about the Bible and coming to understand what he presents as a far more complex reality. How complex? Well, Stanley argues that we must know that biblical references to the Scripture “did not mean the Bible.”

Read the rest from Dr. Albert Mohler

The Dean Recommends: Beyond a Memorialist-Lite Understanding of the Lord's Supper

Many Baptists, Free Church members, and, in modern times, even confessional Reformed Christians don’t give much thought to what is actually going on when we come to the Lord’s Table. We tend to default to a “memorialist-lite” understanding of the Lord's Supper. This is less than the type of memorial that Zwingli and Anabaptists had in view. It is more like a sentimentalist view, where mere bread and wine are intended to make us feel something when we think about the death of Jesus--usually either the “warm-and-fuzzies” or some sort of introspective guilt.

Most Christians throughout history have had a very different view. Even though they saw the problems with the Roman view of the Eucharist, virtually all Protestant traditions have affirmed that when we come to the table of the Lord, we are participating in the very body and blood of Jesus; our real spiritual union with him is nourished and strengthened.

Baptists are no exception to this high view of the Lord’s Supper. The 1689 London Baptist Confession states that in the Lord’s Supper, Christians “ really and indeed, yet not carnally and corporally, but spiritually receive, and feed upon Christ crucified” (30.7). This same article is not afraid to affirm the real spiritual presence of Christ in the Supper: “the body and blood of Christ being then not corporally or carnally, but spiritually present to the faith of believers in that ordinance, as the elements themselves are to their outward senses.” That is, we are spiritually present and united to him in a unique way when we come to the Table. Perhaps it is more accurate to talk about our real spiritual presence with Christ in communion. In any case, Christ is really and truly present with his people at the Table.

Read the rest by Chris Bruno at the Center for Baptist Renewal.

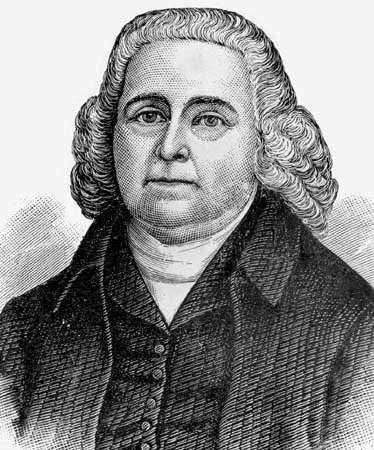

The Dean Recommends: Isaac Backus: An 18th-Century Evangelical with 21st-Century Wisdom

Isaac Backus may be the most interesting and influential American you’ve never heard of.

At the peak of his career, Backus (1724–1806) rode thousands of miles per year to preach to and encourage Baptist congregations throughout New England. In one five-month span, he rode 1,251 miles and preached 117 sermons. He operated outside Baptist circles, too. He debated some of the founding fathers of the United States and was part of the Massachusetts convention that ratified the Constitution. He wrote a three-volume history of New England and sent it to President George Washington as a “private token of love.” Backus is the only person I know of who was both groom and minister in his own wedding.

Backus was also profoundly influential, though he has never shared the renown of his more notable contemporaries. All the traveling and preaching he did in the decades before and after the American Revolution helped organize a Christian fringe group—the Baptists—into a unified movement. A century or so after his death, Baptists became America’s largest and most influential Protestant denomination. Furthermore, Backus drafted a bill of rights for America’s proposed constitution that bore a striking resemblance to the one that was eventually adopted, especially in its protection of religious liberty. He turned Jonathan Edwards’s heady theology of original sin into a practical and political theology of religious toleration. The historian William McLoughlin has claimed that the system of church-state relations that governed America until the last generation or so was precisely what Backus envisioned and worked his entire life to establish.

I like to think of Isaac Backus, the unschooled pastor from Connecticut, as the Forrest Gump of American religious history. The comparison breaks down, but just as Forrest Gump gave moviegoers a peek into the defining moments of a generation—from Elvis Presley’s gyrating hips to ping-pong diplomacy—so Backus interacted in remarkable ways with some of the most important figures and events of his generation.

All this is reason enough for us to know Backus better. But he is more than a figure to admire from a safe chronological distance. He is also someone whose example we can, and should, emulate today. Most of Backus’s opinions were unpopular in his generation. He spent his lifetime swimming upstream and fighting for liberties he was never able to enjoy. In light of the challenges Christianity faces in the first quarter of the 21st century, Backus is a useful figure who can help us look forward by first looking backward.

Read the rest by Brandon O'Brien at Christianity Today.

The Dean Recommends: A Letter to an Aspiring Theologian

I was delighted to receive your letter asking about the best route to becoming a theologian. Let me confess up front: I’m still in via myself. My business card should identify me not as research professor but perpetual pupil of theology, though if it did, you probably wouldn’t be writing to me. I need to underline the point: Theology is neither a nine-to-five job nor a career. To know and speak truly of God is a vocation that requires more than academic or professional qualifications. The image you should have in mind is not the professor with a tweed jacket, but rather the disciples who dropped everything to follow Jesus. Becoming a theologian means following God’s Word where it leads with all one’s mind, heart, soul, and strength.

Let me say a few more things about what theology is and why it matters, just to make sure we’re on the same page. Theology is the study of how to speak truly of God and of all things in relation to God. But theologians can’t approach the object of their study the way biologists study living creatures or geologists the earth. God cannot be empirically examined. God is the creator of all things, not to be identified with any part of the universe or even with the universe as a whole. Speaking of God thus poses unique challenges. If God had not condescended to communicate to creatures something of his light, we would be in the dark.

Are you familiar with Thomas Aquinas’s definition? “Theology is taught by God, teaches of God, and leads to God.” It’s worth pondering these three prepositions.

By God. Only God can make himself known. There is a prior divine self-communication to which all theologians are accountable. You can’t deploy God’s name simply to add support to your pet ideas or favorite agenda. Theologians aren’t fiction writers, either: We’re not making this up, Marx, Freud, and Nietzsche notwithstanding. We’re simply children who love their father and want to know him better, who trust their father’s wisdom (Matt. 18:3), and, for that very reason, keep asking “Why?” (this is my gloss on Anselm’s famous definition of theology as “faith seeking understanding”).

Of God. There are theologies of marriage, the body, leisure, the imagination, and so forth, but they are theological only to the extent that they relate their objects to God, their author and finisher. Theology is thinking hard about what God has taught about himself and all things in relation to himself.

To God. William Ames, a Puritan, uses language much like Aquinas’s: “Theology is the doctrine of living to God.” Theology is more than an academic exercise, more even than knowing God; it’s ultimately about cultivating godliness, in oneself and one’s community. Theology’s proper ends are both contemplative (I dare not say “theoretical”) and practical.

Read the rest from Kevin Vanhoozer at First Things.