“And do not get drunk with wine, for that is debauchery, but be filled with the Spirit, addressing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody to the Lord with your heart, giving thanks always and for everything to God the Father in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, submitting to one another out of reverence for Christ” (Eph 5:18-21).

Psalms, hymns and spiritual songs have been central to Protestant worship ever since the Reformation. They have always been a part of Christian piety, of course. But during the 16th century, they came to play a much greater role than ever before in history. And during and after the Great Awakening of the 18th century, they were used to animate special seasons of revival and renewal in the churches of most denominations and in most parts of the world.

Martin Luther loved to sing. In fact, he sang for his supper as a boarding school student before growing up to champion the singing of hymns in worship. He played the lute as well as the flute. He reformed the Catholic liturgy and penned three dozen hymns, saying “next to the Word of God, music deserves the highest praise...let this noble, wholesome, and cheerful creation of God be commended.”

Some other early Protestants forbade musical instruments and visual art in worship. They instituted what they called the “regulative principle,” which stipulated that anything not taught or found in Scripture should be banned from Christian worship. As a result of this rule, even groups like the Puritans sang the Psalms a cappella and resisted the rise of hymnody for many years to come.

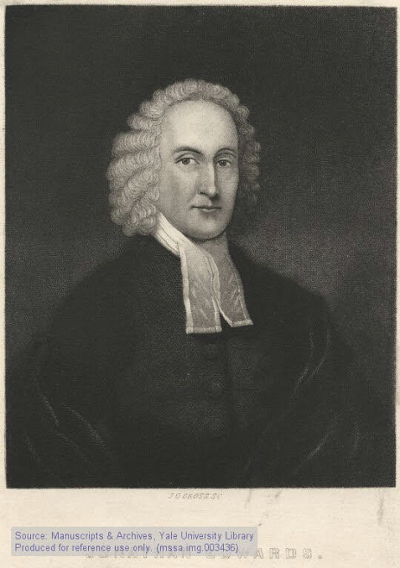

But during the 18th-century revivals, many post-Puritan pastors, such as New England’s Jonathan Edwards, permitted hymn singing—and even taught their people to read music and sing songs in parts. And, during the seasons of revival and renewal that would follow and contribute to the rise of the evangelical movement, hymnody and spiritual songs became a favorite practice of believers everywhere.

In the face of conservative critics who opposed hymn singing in favor of the use of psalms only during church, Edwards wrote this defense of hymns and spiritual songs in worship:

“I am far from thinking that the Book of Psalms should be thrown by in our public worship, but that it should always be used in the Christian church, to the end of the world: but I know of no obligation we are under to confine ourselves to it. I can find no command or rule of God’s Word, that does any more confine us to the words of the Scripture in our singing, than it does in our praying; we speak to God in both: and I can see no reason why we should limit ourselves to such particular forms of words that we find in the Bible, in speaking to him by way of praise, in meter, and with music, than when we speak to him in prose, by way of prayer and supplication. And ‘tis really needful that we should have some other songs besides the Psalms of David: ‘tis unreasonable to suppose that the Christian church should forever . . . be confined only to the words of the Old Testament, wherein all the greatest and most glorious things of the Gospel . . . are spoken of under a veil, and not so much as the name of our glorious Redeemer ever mentioned, but in some dark figure, or as hid under the name of some type.”

If a serious post-Puritan like Edwards could say this, the flourishing of hymnody was just a matter of time. Indeed, the rest is church history. Fervent preaching, discipleship, missions and hymnody have proceeded hand in hand ever since the 18th century—drawing on the cultures of believers everywhere, especially those descended from west and central Africa that contributed to spirituals, gospel music and CCM—constituting the staples of revivals and regular worship services across the globe.

In chapel this past spring, we have given our attention to “Art and Beauty in the Bible.” We have explored some of the things that God has shown us in his Word about his beauty, or glory, the beauty of the cosmos and the ways in which he wants us to reflect and cultivate divine beauty in our lives. We have prayed that the Lord would help us all to grow more beautiful by dwelling on his beauty.

One of the fruits of this emphasis has been that our own corporate singing has grown more beautiful. I am nearly brought to tears most Tuesday mornings as our students lead our people in singing songs of praise to our Maker and Redeemer. God has really been glorified in spirit and in truth.

My prayer for this edition of our Beeson magazine is that it, too, will inspire us to magnify the Lord in our singing—and our everyday lives. May the Lord be praised in what follows in these pages and, more importantly, in the beauty of our everyday conduct “as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is [our] spiritual worship” (Rom 12:1).

Douglas A. Sweeney is dean of Beeson Divinity School and author of The American Evangelical Story: A History of the Movement and The Suffering and Victorious Christ: Toward A More Compassionate Christology.

Notes

Martin Luther, “Preface to Georg Rhau’s Symphoniae iucundae,” a collection of 52 motets (or “Delightful Symphonies”) published in 1538 by a musician friend andfollower, in Luther’s Works, Volume 53: Liturgy and Hymns, ed. Ulrich S. Leupold (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1965), 323-24.

Jonathan Edwards, Some Thoughts Concerning the Present Revival of Religion in New-England, in The Works of Jonathan Edwards, Volume 4, The GreatAwakening, ed. C. C. Goen (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972), 406-407. r, “Preface to Georg Rhau’s Symphoniae iucundae,” a collection of 52 motets (or “Delightful Symphonies”) published in 1538 by a musician friend and follower, in Luther’s Works, Volume 53: Liturgy and Hymns, ed. Ulrich S. Leupold (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1965), 323-24.