Samford University hosted its second biennial conference on Teaching the Christian Intellectual Tradition Oct. 6–8. The conference series is designed to encourage excellence in undergraduate teaching across the curriculum, with a particular emphasis on core curriculum and general education courses.

This year, it brought together almost 100 people, including scholars from 15 institutions, to think about how to help students understand the importance of the Protestant Reformations. University Professor and conference cochair Chris Metress said it was also an opportunity for participants to question assumptions about the Reformations, test them to see if they hold up and possibly to rethink them — to do for themselves “what the very best teachers do” for their students.

Reformations scholars R. Ward Holder of St. Anselm College and G. Sujin Pak of Duke Divinity School presented keynote addresses. Breakout sessions explored aspects of the Reformations ranging across a variety of subjects and disciplines.

David Barbee, a session presenter from The University of Findlay’s Winebrenner Theological Seminary, said that even some seminary students lack the historical context of the Reformations. He said he hoped to take home some ideas about using literature to help them engage with the subject.

Many Samford core curriculum faculty took part in the conference, including Bridget Rose, who has a unique perspective on the challenges of teaching the Reformations. “I’m interested in the Christian intellectual tradition, personally, but I think the value of the conference for me is the focus on teaching,” Rose said. “In my role as director of the Academic Success Center, I see that students’ experiences in a Cultural Perspectives (CP) class can have an impact on their first-year success,” she said.

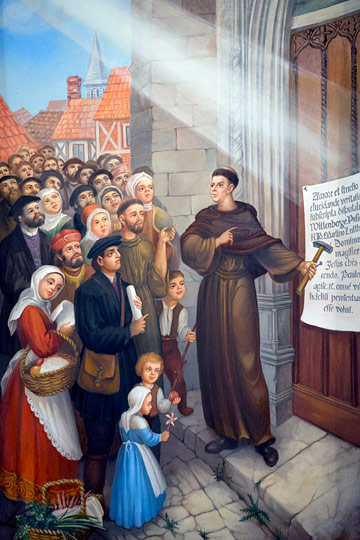

For Rose, former curator of Beeson Divinity School’s Hodges Chapel, helping her CP students have a positive experience with the Reformations includes guiding them through that sacred space. The point is partly to show students the Reformation figures depicted in the chapel, but mainly to help them understand how that space represents a unique perspective on what they’re learning in class.

“The same skill set that I want students to take to a text, I also want them to take to space and works of art, because then they’re learning a skill, not just learning how to answer the questions,” Rose said. “I have them read the space.”

Rose did the same in a special session for conference participants, challenging them to think about how they would use Hodges Chapel or their own institution’s spaces to help 21st-century students connect with a 500-year-old theological revolution. She noted that Beeson Divinity School Dean Timothy George has called Hodges Chapel “a sermon in stone.” It also can be an “interactive lesson plan,” she said, and a unique way to enrich the study of the cultural milestone under examination at the conference.