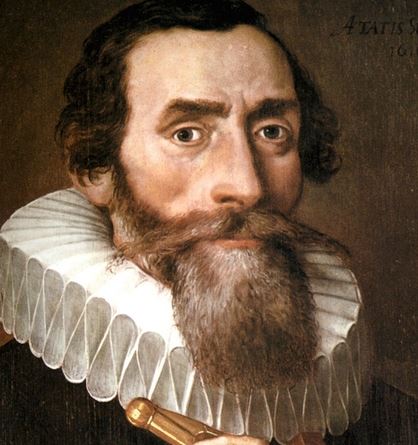

Tycho’s great disciple and the finisher of his work, Johannes Kepler was an astute mathematician and astrologer (that’s right – astrologer). He dwelled on an island of apparent political peace though he was surrounded by the turmoil of religious upheaval in the Counter-Reformation; he almost always had a job and a relatively safe place to live. Interestingly, desired by his employers principally for his abilities to create astronomical calendars and to make horoscopes, Kepler largely spent his time on other projects, while not neglecting to do his paid work with ease. One of these projects, though he may not have ever viewed it as a single endeavor, was the development of the laws of planetary motion, published in a few separate books defending and expounding the Copernican theory of planetary motion.

The first law is this: “Planets move in ellipses with the sun at one focus.” The laws may be said to be unified by Kepler’s desire to describe planetary motion as a result of forces rather than a formulaic statement of geometry. When Brahe (and thus Kepler, who had all of Brahe’s data) saw that the heavens were not “perfect,” unchanging spheres (please look at the Brahe post) a world of possibilities opened. The “perfect” geometry no longer governed the motions of the heavens, and the sun, exerting forces on the planets, guided their seemingly irregular movements. The justification of the first law came partly via discovery of the second law, (both of) which will be described in detail in a future post.