Samuel Sterling Sherman

1842-1852

Samford's first president, 27-year-old Samuel Sterling Sherman, was a native of Vermont who had come south to improve his frail health. He opened a preparatory school in Tuscaloosa, tutored in ancient languages at the University of Alabama and served as UA's librarian. His reputation attracted the attention of those searching for a president for newly-founded Howard College in Marion.

Sherman accepted the presidency of Howard College in spite of the UA president's warning that the Baptists wouldn't be able to sustain their new school. This was an act of great faith, because when Howard College opened in 1842 it consisted of a single wooden building and had no students, no faculty and minimal resources. The curriculum was so limited that when the local newspaper prepared to announce the opening of "Howard University," Sherman went to the printing office and changed the copy to read "Howard English and Classical School"--a more modest and accurate description of the college.

By the end of the first year of operation, Howard College had 31 students. For most of that year, Sherman was the college's only professor, and the combined revenue from tuition was not enough even to pay his room and board. It is said that Sherman had to push a wheelbarrow door to door in Marion begging for books to create a library for the college.

Conditions at Howard gradually improved in the decade of Sherman’s presidency, and he felt it was time to move on in 1852. He visited Marion again after the Civil War, and was celebrated for the kindness he showed in visiting Confederate prisoners of war in Federal prisons, and for his service to Howard College.

Henry Talbird

1853-1863

Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry

1865-1868

Edward Quinn Thornton

1868-1869

Howard College struggled to secure long-term leadership after the Civil War, running through several presidents in quick succession. Howard College professor Edward Quinn Thornton was among them, serving from July 1868 through the end of the 1868-1869 session.

Thornton was listed as Howard College's fourth president as late as 1894, but at some point in Samford's history he simply disappeared from collective memory. Historian Mitchell Bennett Garret recorded his presidency in his Sixty Years of Howard College, 1842-1902, and James F. Sulzby used Garrett's information in his two-volume Toward A History of Samford University, but Thornton is otherwise overlooked. For decades, he has been excluded even from Samford's official tally of its fully-empowered presidents (as opposed to those who served in an interim capacity).

Before serving Howard College as a professor of chemistry and modern languages, Thornton studied at the University of Alabama and at various European universities. He was among the many professors, administrators and students who left Howard to serve in the Confederate States Army, rising from the rank of lieutenant in the 39th Alabama Infantry regiment to become an assistant adjutant general. He returned to Howard only a few years before his elevation to the presidency.

Eight months before selecting Thornton as successor to the high-profile J. L. M. Curry, the trustees of the college announced to the state Baptist Convention that, "the unparalleled prostration of the financial affairs of the country has fallen with particular severity upon the college." By July 1868 the trustees had abandoned hope of building the college's endowment and asked of Thornton, apart from tending the college's property, only that he make the college self-sustaining. They stepped back even from this goal, finally agreeing to Thornton's counter-offer to obtain only sixty of the 100 students required to make the college self-sustaining, with the trustees taking responsibility for the remainder.

The college enrolled 115 students for the 1868-69 session even though Thornton established rigorous new entrance examinations in English, Latin, Greek and Algebra. Though apparently successful, Thornton found that he preferred the classroom to the presidency and resigned at the end of the session to focus on teaching both at Howard and across town at Judson College. His brief tenure seems to be the cause of Thornton's ultimate disappearance from the official roll of Samford presidents.

Samuel R. Freeman

1869-1871

Like E. Q. Thornton, Samuel R. Freeman served as president of Howard College for only a brief time (1869-1871) as the college struggled to find stable leadership after the Civil War. Freeman, an alumnus and trustee, was recommended for the presidency by a fellow trustee who had just declined Freeman's offer of the position. Though surprised by the turned-table, Freeman accepted the presidency.

The trustee who nominated Freeman for the presidency described the Tennessee native as "majestic in structure, towering in intellect, full of Holy Ghost Power." Freeman also suffered throughout his life from a debilitating eye disease but found some comfort in the home of the widow with whom he boarded while a student at Howard. Freeman married the widow, became a leading minister in the state and, as chairman of the education committee of the Alabama Baptist Convention, played a key role in persuading Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry to accept the presidency of the re-opened Howard College in 1865. Freeman joined Howard's board of trustees only a year before following in Curry's footsteps.

Freeman delighted in the new opportunity to serve the college, and dedicated his attention to increasing enrollment and re-opening Howard's Theological Department, which had ceased operation along with most other college functions during the war. He succeeded in the latter endeavor, but a one-year increase in enrollment failed to improve the college's financial picture because so many students made their way through Howard on scholarships, IOUs or irregular payments for tuition. Enrollment dropped to previous levels in Freeman's second year in office, leaving the college in ever-deepening debt.

By 1871, Freeman had seen enough of life as a college president. Deciding, like E. Q. Thornton, that his true calling lay in his original profession, he resigned the presidency in favor of full-time ministry in Jefferson, Texas. He died only a year later, just as his alma mater entered a period of dramatic and sometimes controversial transformation under the long-term leadership it had sought for a decade.

James T. Murfee

1871-1887

James T. Murfee's tenure as president of Howard College (1871-1887) was exceptional in many ways, not least because Murfee didn't leave the college--the college left him. At 16 years, his service also was of exceptional length. In fact, Murfee's record as Samford's longest-serving president stood until the 1950's. His administration remains the fourth longest in the University's history.

Murfee, a native Virginian and alumnus of Virginia Military Institute became a professor of mathematics at the University of Alabama before the Civil War and served as both a lieutenant colonel of the 41st Alabama Regiment and commandant of the University of Alabama cadet corps. Reconstruction-era politics made Murfee feel unwelcome at UA after the war, so he brought his reputation for academic rigor and military discipline to struggling, debt-ridden Howard College in 1871.

Murfee seems to have thoroughly charmed the people of Marion, and he certainly supplied stable leadership to the college for the first time in over a decade. He revitalized the academic program by creating a new academic structure based on small class size and individual attention and practice, and created a Business School and a School of Military Art and Science within the college.

He also imposed military discipline. Beginning in 1871, Murfee required students to wear gray military uniforms on public occasions. By the end of that decade military drill was a daily routine for many students and the college had begun to resemble a military academy.

Renewed appeals for financial support led the college out of debt by the early 1880's and even allowed the addition of new property, but the trustees' voiding of scholarship certificates sold before the war led to an eight-year breach of contract lawsuit against the college. That action ended in 1883 with a judgment for the plaintiff and a court order to auction off the college's property on the steps of the county courthouse to meet the resulting financial obligations. In 1884, two Howard trustees bought the college property at auction for $1,080 and presented the property to the Alabama Baptist Convention.

With outright ownership and no remaining debt, the Convention saw that it might finally be able to build a solid endowment for the college. But some Howard supporters outside the county feared that new investment would be wasted in a waning Marion and with the college under the control of Murfee and the college's local trustees, who increasingly found themselves at odds with the Convention.

Ongoing disputes with the Convention over the status of ministerial students and religion faculty ended in 1886 with a victory for Murfee's insistence that Howard would not exempt ministerial students from the college's military and residence requirements, and would not allow the Convention to dictate faculty appointments. The entire ministerial board of the Convention resigned in protest, adding to growing tensions between the college's administrators and owners.

Also in 1886, increasing racial tensions in Marion erupted when Howard cadets surrounded and beat a black student from Lincoln Normal School, the student cut some of the students with a knife and a mob of white citizens subsequently threatened to burn down the school founded at the end of the Civil War to educate newly freed slaves.

Lincoln was already pondering whether or not to stay in Marion or move to Montgomery or Birmingham, and the conflict with Howard actually bound together Lincoln's and Howard's fortunes. Lincoln supporters closely followed the growing debate among white Baptists over whether or not to move Howard, and Howard's trustees, largely opposing the relocation of their own school, circulated a petition calling for the removal of Lincoln Normal School from Marion.

In a telling letter to the Marion Standard newspaper, the editors of the Alabama Baptist explained why they had refused to print an article citing the Howard-Lincoln trouble as sufficient reason for moving Howard. "Just at that time the citizens of Marion with people all over the state, representing the Baptist, Methodist and Presbyterian churches were earnestly laboring with the legislature to have the negro normal school removed from that place," they wrote, "and it was gravely questioned as to whether or not they could succeed, and our judgment was, that should such an article...appear [about moving Howard College]...many members of the general assembly would refuse to vote for the removal of the negro college, and thus fasten on a long established white school community an institution [Lincoln] that was a positive menace to virtuous womanhood and helpless children."

So, race played a part in the debate about removing Howard College from its birthplace, but the college also was caught up in the tensions between rural and urban cultures and new and old economies and social structures. Murfee found himself at the center of this storm.

As Murfee fought with the Convention over the fate of the ministerial students, the Convention considered relocating the college and all parties warily eyed Lincoln Normal School, Birmingham boosters were searching for new institutions to serve their 15-year-old community. In 1886 the Convention met in Birmingham and appointed a committee to open talks with Birmingham land companies and consider the city's generous incentives for relocating Howard College to the area. Following rich promises of land and financial support, Howard College relocated to Birmingham's East Lake community in 1887.

The Marion Standard expressed outrage at Howard's removal. "A great act of injustice has been done the Baptists of Marion, who have so long and so faithfully worked to sustain the college, when the Baptists of North Alabama were doing nothing," the editors wrote. "If another school is established in its place, Marion will not be injured a particle by the removal of Howard College." In fact, another school literally was established in Howard's place. The Convention returned the Marion property to the two trustees who had bought it at auction, and asked them to use the campus for the good of Marion. James Murfee, the only member of Howard's faculty who declined to follow the college to Birmingham, leased the college property for a year and established Marion Military Institute. The institute thrived and Murfee eventually acquired the property in trust from its owners.

In spite of his own misgivings about the removal of Howard, Murfee acted as peacemaker between Baptist factions divided by the move. In contrast to the bitterness and hurt feelings expressed by the Marion Standard, a letter from Murfee, published in the Alabama Baptist of August 5, 1887, expresses nothing but good will for Howard and its alumni:

To My Old Students and Friends

These halls so dear to us all have been turned over to me for educational purposes; and I shall continue in them the same system of discipline and methods of instruction which I introduced in 1871.

I shall aim to train other young men as you were trained, and to make them like you in character, popularity and usefulness. The memory of your good deeds shall be preserved, and your worthy examples held up as models for your successors.

The hearts of the good people of Marion will ever be with you; and we hope you may often be inclined to revisit the old college home--the scenes amid which you developed those elements of character which have been the foundation of your success and happiness. You will find here open doors and a warm welcome--in the town and at the school.

Whenever an opportunity occurs, I shall rejoice to assist in extending your influence and promoting your welfare.

Ever Your Friend

J. T. Murfee

In the short term, at least, Murfee and other opponents of Howard's relocation were vindicated. Howard College arrived in Birmingham to find that the city's generous promises of support had evaporated.

Benjamin Franklin Riley

1888-1893

Benjamin Franklin Riley served during one of the many precarious periods in Samford's history. When Howard College relocated to the East Lake community of Birmingham in 1887 it left behind its president and several trustees, not to mention the good will of some Alabama Baptists. Worst of all, the trustees discovered that an important section of the new campus site was not included in the donation of the East Lake Land Company, so they immediately had to purchase that additional property. Also, in spite of the land company's grand dreams, there was little in the rural area surrounding the new campus apart from Ruhama Baptist Church, which would serve as the spiritual home of the college through the 1950's, and the old school building of the defunct Ruhama Academy.

The economic bubble that led Howard College to Birmingham had burst and the school found itself once again in dire financial straits. Visions of a rich endowment and grand new facilities faded as the trustees realized the college's two temporary buildings would have to serve longer than expected. One trustee, a supporter of the relocation, proclaimed, "Well, if I had known that we were not to have buildings, I should never have voted for removal."

Historian Mitchell Bennett Garrett paints a vivid and unflattering picture of the campus in those early years in East Lake.

At the college, the scene was anything but inviting. Two wooden buildings of hasty construction stood wide apart in a growth of old field pines. The surroundings were uncleared of underbrush, and the trees which had been felled more than a year before to make room for the buildings were still lying about the grounds. The remnants of the library were scattered and torn over the floor of an outhouse; pictures and broken furniture were piled in the corners of the limited hallways; the furniture of all the departments was old and rickety, the bedding inferior and worn.

Howard's trustees had the unenviable task of persuading someone to preside over that uninspiring scene. Three nominees declined the presidency before B. F. Riley agreed to lead the college in September 1888.

Riley, the son of a Pineville farmer, was Samford's first native Alabamian president. The graduate of Erskine College, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and Crozer Theological Seminary was a well-known pastor, editor of the Alabama Baptist newspaper and author of many books on Alabama history. After accepting the presidency, he acted quickly to stabilize and expand the college, refurbishing the old Ruhama Academy building, purchasing milk cows and planting a garden to supply the campus dining hall. He emphasized the moral as well as the academic and martial education offered by the college but, not surprisingly, seems to have focused most of his attention on staving-off financial catastrophe.

By 1889 college officials had grown so tired of Birmingham's failure to provide all it had promised that they openly investigated abandoning East Lake. Howard's financial outlook was so grim during this period that one financial agent resigned and his replacement remarked, "There are 75 men in this city who say they will give, but they all want to be the last, and how to make the whole 75 last is a mathematical problematical problem I have been unable to solve, after days and days of thinking."

In spite of the hard times, the college pressed ahead on construction of a brick multipurpose building. The new building, completed in 1891 and later known as "Old Main," was the architectural centerpiece of the new campus. New dormitories and other improvements followed soon after, but Howard's rural setting remained less than impressive. J. J. Finklea accompanied his son to college in 1891, and as the pair approached the campus on foot the father asked, "My boy, how much farther? Are we not about at the place?" "Yes, Papa," his son replied, "this is the place." Finklea considered the tangle of pines and brush before him and said, "but I didn’t know, my boy, that you were camped here in the woods."

A nationwide economic depression reduced Howard's enrollment in 1892 and Riley traveled around the state at his own expense to recruit students. Unfortunately, many of those he recruited required extra time in paying tuition, forcing the college to borrow funds for the year. Riley noted midway through the 1892-93 session that although the college had not succumbed to despair, "there has been an appreciation of an ever-increasing weight of responsibility, the appreciation of a burden growing heavier and heavier, and one which, in the nature of the case, is growing still more heavy as the session advances."

Riley held out hope that the people of Birmingham would help the college in its time of greatest need, especially since he calculated that Howard had contributed at least $60,000 to the growth of the city since the college's arrival in East Lake. But by early 1893 a fundraising campaign in the city had netted only $500 of the $2,000 needed to continue operating the college. "The sources from which I have derived means to tide the college over the 'trying' periods of the past five years have now been exhausted," Riley lamented.

Riley himself seems to have been exhausted by the financial struggle. He proposed hiring a full-time field agent to represent the college in securing both students and endowment funds. Alternately, he said, the college could call on Baptist women in the state to raise money to build tenant houses on the campus. He thought the latter project could provide rent and a pool of prospective students as well as increase the value of campus property and harness the considerable influence of Baptist women. The Trustees did eventually follow Riley's advice about the full-time field agent, but by that time Riley had already moved on. He resigned at the end of the 1892-93 session in order to accept a position as professor of English literature at the University of Georgia.

In spite of the financial frustrations of this period and thanks to Riley's extensive recruiting efforts, the class of 1893 was the largest in the college's history. Howard's next president would make history as well, but with the addition of only five students.

A. W. McGaha

1893-1896

B. F. Riley, in his brief years as president of Howard College, managed to keep the institution open and supplied with students. A published letter of the period heaped praise on Riley and set overly optimistic expectations for his successor. "It seemed to have been necessary from unavoidable environments and the decree of a benignant Providence," B. H. Crumpton wrote of Riley, "that he should have commanded the ship and planned the voyage, until his youthful, symmetrical and brilliant successor, A.W. McGaha, D.D., one of the grandest sons of his honored Alma Mater, like some luminous star, arose in the wane of departing night, to herald the advance of day."

Arthur Watkins McGaha, the son of a Marshall County, Alabama, farmer, was the first alumnus president of Howard College. After earning his Howard degree in 1881, he attended Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, pastored two churches and accepted the call to lead Ruhama Baptist Church shortly after Howard College relocated to property adjacent to the church. This was a critically important time in the lives of both Howard and Ruhama, and the institutions bound together their fortunes. The church provided a spiritual home for the college as well as a deep well of leadership from which to draw staff, faculty and students. Likewise, Howard College brought to East Lake scholars who served Ruhama Baptist Church as well as they served the college.

Upon taking office in June 1893, McGaha took up perhaps the greatest burden his friend B. F. Riley had carried--recruiting enough students (in the midst of a nationwide economic crisis) to allow the college to operate. McGaha failed, but the college opened on schedule that fall, albeit slipping further into debt.

The college's financial picture was so grim that the board of trustees openly castigated themselves for their failure to improve it, even going so far as to suggest that the Alabama Baptist Convention replace the entire board. The board remained but, acting on suggestions made by Riley, the Convention and Howard alumni, hired a full-time vice-president/financial agent to travel the state raising funds and recruiting students. The agent's success allowed Howard to make needed building repairs and improvements while the students, working voluntarily, also made great improvements to the campus grounds.

By the spring of 1894 Howard was physically much improved. Its fiscal health was another matter, although the new financial agent had secured promising new pledges of support. The year's decreased enrollment, indicative of a dangerous downward trend, was of special concern. This problem may have played some role in Howard's first experimentation with coeducation, led by McGaha.

Coeducation was already reshaping the culture of other Alabama colleges. Some Alabamians opposed this trend, but McGaha and his supporters persisted and prevailed. College records of the period suggest no great disruption resulting from the admission of two East Lake women, Annie Judge and Eugenia Weatherly, for the 1894-95 school year. In fact, some male students who looked forward to a soothing feminine influence on the toughest members of the faculty lamented the lack of change in their professors. The women proved to be excellent students, and they were followed by three more female students in the 1895-96 school year. Unfortunately, the addition of these few women was not sufficient to help the college out of its growing debt.

By the end of that academic year, the college had defaulted on its mortgage payments and for the second time in a little more than a decade faced the humiliation of a forced public auction of the campus. At the annual trustee meeting in June 1896, just weeks before the scheduled auction, McGaha noted that the college lacked the funds to pay its employees and proposed a radical, if temporary, solution. "The college can ill afford to stand the salary list as it is now paying," he told the trustees. "The institution can dispense with the president more easily than any professor," he added. He offered his resignation and the trustees immediately appointed professor A. D. Smith "chairman of the faculty and manager of the college."

Like Howard president Samuel R. Freeman, McGaha returned to full-time ministry. Like Freeman, he eventually resettled in Texas. As pastor of the First Baptist Church of Waco, he led the largest congregation in the Southwest. But, like Freeman, McGaha died not long after leaving the college. Upon his death in 1901 he was recalled with great respect by his predecessor, B. F. Riley. McGaha, he wrote, "possessed a combination of qualities rarely found in a man because of his boldness and tenderness, frankness and sympathy, courage and gentleness--all these were called into exercise and expressed as occasions demanded--these enabled him to reach a far larger class of people than are ordinarily reached by any one man."

Coeducation at Howard faltered after McGaha's departure, but another pastor/president helped realize that bold vision a little over a decade later. But what of the financial catastrophe threatening Howard College at the time of McGaha's resignation? Rather than leaving the college without leadership at a moment of crisis, McGaha's decision may have helped save Howard. His successor, though understood to be merely a caretaker president, arranged for a financial rescue almost as dramatic and improbable as that of 1884.

A. D. Smith

1896-1897

As a professor of mathematics and longtime business officer of Howard College, Albert Durant Smith must have been acutely aware of just how dire the college's circumstances were when he became president in the summer of 1896. The school's finances had driven away the previous two presidents and the end of the college seemed to be in sight. Howard's trustees appointed Smith "chairman of the faculty and manager of the college" less than two weeks before the college's property was to be foreclosed upon and publicly auctioned by the owners of its mortgage.

Smith, a native of Georgia, had served Howard College in many capacities since arriving at the Marion campus in 1881. In addition to his service as a mathematics professor and business agent, he was a famous disciplinarian who had commanded the cadet corps under the watch of President J. T. Murfee. The latter experience served Smith well as he took up the challenge to save Howard, make it self-sustaining and free it of crippling debt.

First and most importantly, Smith persuaded his friend, Birmingham banker Burghard Steiner, to personally guarantee payment of a significant part of Howard's debt if the college's creditors would agree to extend payment deadlines. The creditors agreed to postpone foreclosure, but Howard was left with the old problem of how to raise the funds to pay its debts. The college turned again to Alabama's Baptists.

At the request of Howard's trustees, three Baptist Birmingham pastors, B. D. Gray, P. T. Hale and W. A. Hobson took months-long leaves of absence from their churches to raise the money needed to save Howard. The $16,000 they raised--half-cash, half-pledge--was sufficient to make up missed payments and prevent foreclosure.

As the pastors undertook their work, Howard resolved a land dispute that had haunted the college since it arrived in East Lake. The East Lake Land Company finally agreed to donate the lots adjacent to the campus that the trustees had understood to be part of the incentive for relocating the college.

As the campus grew, Smith continued and enlarged the improvement projects begun by his predecessor, A. W. McGaha, adding new sidewalks and renovating buildings. The college still lacked necessary facilities, however. Citing the lack of appropriate facilities for women, Smith discontinued the experiment in coeducation that had given Howard its first female graduate, Annie Judge, in 1896. Of the other women enrolled at the college, only one somehow continued her studies after the announced end of the experiment. Eugenia Weatherly graduated in 1898 with the first full, four-year Howard degree awarded to a woman. She would be the last female graduate for almost two decades.

The temporary end of coeducation corresponded with Smith's application of an almost military discipline to the daily life of the college. This included the creation of a student "officer of the day" and the strict regulation of time and tasks. Significantly, the students were allowed to visit nearby Birmingham for only four hours each Saturday morning. One of the great selling points of the college, it seems, was that it was removed from the notorious "demoralizing agencies" of the young city. According to one observer, "every boy goes from chapel directly to his work. There is nothing but business through the whole day. Everything is done in systematic order."

Smith's administration sounds harsh to modern ears, but it seems to have inspired confidence and investment. A Howard College Day collection in the state's Baptist Churches in early 1897 further reduced the college's debt and gave hope that Howard could soon be debt-free.

By the end of the spring session, in only a year of service as president, A. D. Smith had led Howard toward a stability it had not enjoyed for over a decade. But, like his immediate predecessors, he'd had his fill of the experience and resigned the presidency in favor of a business career. For the fourth time in a decade, Howard sought new leadership.

Frank M. Roof

1897-1902

President A. D. Smith left Howard College on a more solid financial foundation than it had enjoyed in decades. His successor, Kentucky-born educator Frank M. Roof, magnified that success many times over and served longer than any president since Howard relocated to Birmingham.

The relatively young new president (only 40 years old when he accepted the presidency in 1897) apparently took a special interest in physical education. He created new student bathing rooms with running hot water and created a gymnasium that the Birmingham News reckoned was "the best organized gymnasium of any college in Alabama." This attention to nurturing the bodies as well as the minds of students quickly became a point of pride at the college.

The tradition of Samford basketball began on Roof's watch, although there was some initial confusion about the rules of the game.

"Every man has his own basket, was the information volunteered by one who, no doubt, was better acquainted with picking cotton than with this new game," reported The Howard Collegian student journal when the sport arrived at East Lake in 1900. According to the Collegian, one visionary student suggested that people might actually pay to view the new sport. Howard fielded its first basketball team--the first college basketball team in the Gulf Coast states--early the next year. In the first intercollegiate game for both teams, Howard beat Auburn University 12-7. Howard created official baseball and football teams soon after the establishment of the basketball team.

Roof encouraged the expansion of the academic program as well, joining the faculty as a professor of psychology and pedagogy, adding botany and extending offerings in psychology, French and German. English was another curricular strong point and one observer reckoned that "the course in ancient languages is the best in the South."

Other important events of Roof's tenure included the establishment of Howard's first official alumni association (1899) and, in 1902, repeal of the college's 26-year prohibition of student fraternal organizations.

Under Roof's administration Howard even managed to achieve one of its most elusive goals. Since glimpsing financial independence at the end of A. D. Smith's presidency, the trustees had held out hope that the college could be entirely free of debt within a few more years. Howard reached that goal in 1899, thanks largely to the generosity of Baptist supporters throughout the state and to Howard's faculty, which for years had funded all building repairs and improvements.

Howard's physical, financial and cultural growth under Frank M. Roof was remarkable considering the grave danger Howard faced only a year before his appointment to the presidency. But he declined the trustees' invitation to continue in the office after 1902. The trustees reported that Roof declined on the grounds that "the salary is not in keeping with the arduous duties which the office requires." Roof began a new career selling real estate and insurance. Howard's trustees, failing to interest their unanimous first choice for Roof's replacement (noted Baptist pastor L. O. Dawson), found the next president among the college's competitors.

Andrew P. Montague

1902-1912

Well-known Alabama Baptist leader L. O. Dawson declined the offer of Howard's presidency after Frank Roof's departure in 1902, as did Furman University president Andrew Phillip Montague, initially. But former president A. D. Smith pressed Montague and finally persuaded him to accept Howard's offer.

Montague, a native Virginian, was by that time a respected classics scholar who had translated, edited and published letters of Cicero and Pliny. He also was a champion fundraiser, and preferred to leave to Howard's faculty much of the policymaking and daily operation of the college so he could travel the state on behalf of the college. This he did enthusiastically and with tremendous success.

Montague seems to have had an uncanny ability to not only envision large new projects, but also to quickly find money to complete them. When he recognized the need for a new library and a building to house it, he simply went out and raised the needed funds. Given the goal of raising $75,000 (equivalent to seven buildings the size of the new library) for Howard's endowment, he found the money seven months ahead of deadline.

Montague's success was due in part to the statewide enthusiasm for Howard nurtured by his immediate predecessors. In particular, Montague found a powerful fundraising ally among the Baptist women of the state. The Howard College Cooperative Society, founded by prominent Baptist women in the Birmingham area, contributed to key Howard goals, including the library and endowment, a new dormitory and curricular expansion.

Although state Baptists can take credit for much of Howard's prosperity during Montague's administration, the president's contemporaries recognized that he was a uniquely energetic leader. One Baptist leader of the day recalled that in order to fund the building of the new dormitory, Renfroe Hall, Montague "literally walked that money down in this district, tramping the streets of Birmingham and the surrounding towns, and came near to walking himself into his grave." In fact, Howard's "invincible president," as The Birmingham News once called him, traveled more than 11,000 miles in Alabama in a single year at one point, gathering both money and students in record-breaking amounts.

Montague's great professional success was tempered with personal tragedy near the end of the 1905-1906 school year, when his wife, May Christian Montague, died of cancer. It was said that she was his inspiration and aid in all his work for Howard, so it was fitting that two weeks after her death, Howard's trustees voted to give her name to the newly completed library building. Montague married a Woodlawn native (Emma Florence Wood) a year later.

Montague continued Howard's recent emphasis on exercise as part of a well-rounded education. "Go in for baseball, and tennis, and other clean, manly sports," he advised the Howard students, and they seem to have followed that advice. The new sport of football attracted greatest interest and enthusiasm. Howard formed its first official football team in the fall of 1902 and played its first intercollegiate football game (a win) against Marion Military Institute, which had literally taken Howard's place in Marion.

The familiar accoutrements of college athletics soon followed. In 1904, Howard's faculty required student athletes to meet a minimum standard of 80 percent in each course of study (or 85 percent if they wished to join more than one team). In 1906, Howard added a playing field behind the college's main building. Howard first offered full athletic scholarships in 1907.

Howard's cadet corps continued to hold an honored position at the college, and the organizers of the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair imported a contingent of Howard cadets to perform military drill exhibitions at the fair. By coincidence, Birmingham's other representative at the fair--sculptor Giuseppe Moretti's statue of Vulcan, the ancient Roman god of fire--today stands only a few miles from Samford's Homewood campus.

Judging from the number of discipline cases and tightened campus rules, Howard students seem to have been increasingly inclined to venture into Birmingham, notorious in those days for its bars and brothels. Those students unlucky enough to be caught drinking alcohol in town were placed under "campus arrest" for months at a stretch, or even permanently.

Howard junior Albert Lee Smith made the best of the official anxiety over the students' city excursions, proposing that he be allowed to operate the first Howard college bookstore beneath the stairs of Renfroe Hall, thus eliminating the need for students to venture into Birmingham for school supplies. Smith, a trusted officer of the cadet corps, took orders for a variety of goods, purchased them himself in Birmingham and sold them for a profit on campus. Howard officials knew a good idea when they saw one, but had the good manners not to take over Smith's operation until after he graduated.

Howard's relative prosperity during this time, its athletics boom, the 1902 repeal of the ban on student fraternal organizations and the subsequent blossoming of fraternities and clubs inspired a new student publication, Entre Nous ("between us"). This annual publication was a rich and unprecedented record of student life at Howard.

So great were Baptist hopes for Howard's future during Montague's time that at the 1906 meeting of the Alabama Baptist Convention future Howard president T. V. Neal proposed that the college's trustees develop a 20-year plan to create a comprehensive "ten-million dollar university," to be called the University of Birmingham, with Howard College remaining at its core. Neal's vision was well-received but wildly optimistic and ill-timed.

Howard's finances became strained again after an economic depression in 1908. In 1910, seeing that Howard's coffers were empty and large debts were outstanding, the faculty reminded Montague that their already meager salaries had often been overdue in recent years. Cash-flow problems, they said, had negatively affected their credit and, by implication, the reputation of the college.

A 1909 policy of collecting fees from students who had to repeat exams served the twin purpose of supplementing Howard's income and encouraging students to pass exams on the first attempt. In 1910 the faculty made more serious recommendations to relieve the financial strain, including calling in all outstanding student debt and requiring almost immediate payment of tuition upon a student's matriculation.

The faculty also required Montague to pass along to the trustees and the state Baptist convention a report of the college's funds and increasing debt. Upon hearing that report, the trustees emphasized that the president and faculty should adjust their work to "the limitation of our income," and as a result Montague made deep cuts in the faculty budget. The endowment, on the other hand, was more than $80,000 and Montague remained optimistic enough about Howard's future to propose construction of a new gymnasium.

Although Montague was tirelessly forward-thinking in terms of the growth of Howard College, he was very much a traditionalist and critic of what he viewed as the secularization of education. In a 1909 sermon at Ruhama Baptist Church, Montague excoriated the faculty of other colleges who, he said, scorned tradition, criticized the national government, disdained religion and either revised the Bible "to suit latter-day scholarship" or discarded it altogether. Two years later he declared that "no professor has the right to force his infidel beliefs on a student, and if I should learn of an instructor in this [Howard] college, who was an infidel, I would immediately call a meeting with the view of having him dismissed." In spite of such strident beliefs, Montague led Howard into partnership with the University of Alabama to create the Alabama Association of Colleges, which promoted improvement of Alabama's schools according to national standards.

Under A. P. Montague, Howard College enjoyed the greatest success of its history, but a decade in one place was enough for the president. Montague resigned his office at the end of the 1911-1912 school year and departed to lead Columbia College in Florida. Howard's next president served only half as long as Montague, but he immediately, radically and permanently changed the culture of the college.

James M. Shelburne

1912-1918

The presidents who preceded James M. Shelburne made significant contributions to the welfare and status of Howard College, but none of their achievements are as visible as Shelburne's at the modern Samford University. Samford's music, education and journalism programs owe their creation to Shelburne. Samford's women students, who now significantly outnumber the men, have Shelburne to thank for establishing coeducation as well.

Shelburne, a Kentucky native with degrees from Georgetown College and Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, was introduced to Howard College via Ruhama Baptist Church, his first pastorate. He served the Howard community as both pastor and professor during the early years of the century but eventually returned to Georgetown to earn a D.D. degree. When Howard College again called on his services in 1912, he was leading a church in Bristol, Virginia.

Shelburne eased into the presidency (and out of it, coincidentally) over a period of half a year. Howard's trustees elected him in the summer of 1912 but he didn't begin his service until January 1913.

Shelburne had strong connections to Alabama Baptist culture through Ruhama, Howard and through his wife, Martha Washington Crumpton, whose parents were highly regarded Alabama Baptists. At 46 years of age, he was 13 years younger than his predecessor. These factors may help explain how he was able to begin his presidency in as energetic and bold a fashion as he did.

Shelburne quickly ended Howard's military education program, a Howard tradition of over three decades, on the grounds that it was declining in popularity and interfered with the college's growing athletics program. More importantly, he arranged for a revolution in the form of the ten young women who enrolled as Howard students on September 11, 1913. From that day forward, Howard College was coeducational. Unfortunately, official records from Shelburne's era are all but silent on the return of coeducation. Perhaps the president had his three daughters in mind when he decided that women should have the opportunity for a Howard education.

Whatever his personal motivation, Shelburne didn't mention coeducation in an open letter to the Alabama Baptist shortly after the college opened that fall. Howard's trustees, in their November 1913 report to the Alabama Baptist Convention, offered only a brief note about the change.

"The college now admits to its classes resident young women," they wrote. "Ten of these young women have matriculated and are proving themselves to be most satisfactory students."

An anonymous student poem in the Entre Nous recorded a certain amount of foreseeable tension in the sudden cultural change.

Shelburne was responsible for many impressive "firsts" at Howard College, and more than a few of these benefited the women students.

In 1915, Howard became the first college in the South Atlantic region to offer journalism courses. Journalism was given departmental status the following year and in that program a number of women gained a professional education unavailable even to most men in the region. The journalism program created Howard's student newspaper, The Crimson, still publishing almost a century later.

Shelburne created the position of Dean of Women to support the coeds as well as teach. In 1915 he appointed to that position Nannie Hiden, who, in an interview with a female student journalist, railed against the injustices of official sexism and predicted the ultimate victory of suffrage even in the conservative South.

In 1916 alone, Lula Mehaffey became Howard's first female graduate since 1898, Howard held its first coed party, and the Howard women formed the college's first sorority (Theta Xi) and its first women's basketball team. The following year, the college's 75th anniversary, Howard College heard its first female commencement speaker.

Shelburne also established Howard's departments of music and education and the first student employment office.

Howard's relationship with the city of Birmingham had sometimes been strained due to both economic and cultural conflicts, but Shelburne promoted engagement with Birmingham, not just through its Baptist churches, but also through its other religious, cultural and economic institutions.

Notwithstanding the old fights with students over the corrupting influence of the city, Howard's leaders welcomed the extension to East Lake of Birmingham's trolley service. Starting in March 1913, Birmingham beckoned at 10-minute intervals, but discipline problems actually seem to have declined. In 1915, determined to create a department of music, Shelburne added to the faculty professional music educators from the city's Southern School of Musical Art. He called on a well-known city bandleader to create and instruct a Howard College band. Shelburne also added to the faculty the Rabbi of Birmingham's Temple Emanu-El, who later served on the college's fundraising committees (it has been said that in fundraising Shelburne promoted the cause of education above the cause of denomination).

Shelburne also led Howard to join the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce, noting that, "Howard wants an active part in the upbuilding of Birmingham, and we want to be more closely identified with the civic and industrial activities of the city."

The War in Europe made "upbuilding" of the college somewhat more difficult after 1914, but the greater problems for Howard arrived after the U.S. entered the war in the spring of 1917.

Enrollment for the fall session dropped 20 percent as male students entered military service. The war ultimately claimed Howard's president as well. In the fall of 1917 Shelburne requested, and was granted, a leave of absence to enter uniformed service and supervise educational programs at Camp Wheeler in Macon, Georgia. College Dean J. C. Dawson managed Howard in Shelburne's absence.

With the president in uniform and Howard's male students preparing for war, the coeds spent their free time making clothing for soldiers in a specially outfitted knitting room in Renfroe Hall. As further contribution to the war effort, Howard undertook to raise as much of its own food as possible, purchasing hens to supply eggs and a mule to plow three acres of campus for vegetable crops.

Shelburne returned to Howard in January 1918 in order to help raise funds for the college's endowment. The fundraising went well, and there was little reason to think that Shelburne would not return at war's end to lead further dramatic growth at the college. But, like other of Howard's pastor-presidents, Shelburne decided in March 1918 that his calling to ministry was greater than his calling to educational administration. He resigned the presidency to serve First Baptist Church of Gadsden. Howard College faced an unsettled few years.

Charles B. Williams

1919-1921

Howard College in the years 1917 through 1921 was greatly unsettled by the war in Europe. J. M. Shelburne took a leave of absence from Howard's presidency in order to serve in the military. After his resignation in March 1918, Howard's trustees appointed dean of faculty John C. Dawson to serve as acting president. But Dawson, too, was soon granted a leave of absence to serve in the U.S. Army Education Corp in France. Mathematics professor Theophilus R. Eagles then served as acting president (or acting-acting president) until the trustees finally secured a new president in mid-summer 1919.

On paper, at least, North Carolina native Charles Bray Williams seems to have been an ideal choice for the presidency of Howard College. According to his daughter, Charlotte Williams Sprawls, Williams was "the scholar in a farm family of six children," who lashed his Latin book to the handles of a plow so he could study while working. By 1919, Williams had made a name for himself as a pastor and as a highly respected scholar and veteran professor of Greek and New Testament. His translation of the Greek New Testament, in progress while he served Howard, was an influential and important work, and remains in print. But, for all that, the Williams administration ended abruptly and bitterly.

Like J. M. Shelburne, Williams sought to link Howard's future to Birmingham's, and his downfall was in leading a campaign to relocate the college closer to the heart of the city. As in the 1880's, supporters of moving Howard questioned the value of investing further in a campus whose isolation and aging facilities were seen to limit the college. Alumni opposed relocation, accurately pointing out that the move from Marion had bitterly divided state Baptists for decades. But faculty and trustees supported relocation, and in late summer 1920 Williams announced that the trustees had selected and purchased options on 120 acres in Woodlawn for a new campus, and had halted investment in the East Lake campus.

As the relocation debate simmered, Williams led a new endowment and debt reduction campaign, succeeding in a short time in eliminating all of Howard's outstanding debt, increasing the endowment to $400,000 and increasing faculty salaries 20 percent. Less than one month later, Williams announced yet another campaign. He proposed to raise an additional $500,000 to create an endowment of almost $1 million.

This, he said, would allow the college to relocate, establish a hospital and a department for the study of medicine, and create "one of the finest technological departments, including a first-class engineering school, in the South." If his vision for Howard's future was off the mark, his vision of Birmingham's was uncanny. "The city needs an engineering school and other technical schools and it needs a great medical school," he said.

Alumni opposition to relocation, combined with the vagaries of the economy, foiled the president's plans for Howard and Birmingham. In early May 1921, Williams announced that he would be away for awhile and then simply never returned to office. There is more than a trace of bitterness in his letter of resignation, published in The Birmingham News several weeks after his departure:

Whereas, it seems impossible, in the face of the terrific financial depression, to raise in the near future the necessary one half million dollars for the moving of Howard College to Woodlawn Heights, according to resolutions adopted by the Board of Trustees; whereas, it is my conviction that my high ideal of the Greater Howard, for the education of thousands of youths for the glory of God, could scarcely, if at all, be realized at East Lake; whereas, I am convinced that under the circumstances, I could not serve God best, or help humanity most, or do my full duty to my family; Therefore, I do hereby tender to the Board of Trustees my resignation as president of Howard College to take effect June 1, 1921.

The letter also provides a tantalizing clue to Williams' sudden departure. "As a true sport I take my hat off to the winners of the game--the East Lake minority," Williams wrote. James F. Sulzby, Jr., on whose research and writing this series is based, noted that "the friends of Howard in East Lake concluded it would be easier to remove Dr. Williams from the presidency than to resist the removal of Howard College from their community." It isn't clear how they accomplished this. Sulzby wrote only that "personal unpleasantries and innuendos had caused Dr. Williams' tenure at the college to become complicated and ineffective." Williams' wife was ill during this period (and died shortly after), and that may have contributed to the pressures that drove him from Howard.

Whatever the cause of Williams' departure, it does not seem to have hindered his career. After leaving Howard he joined the faculty of Mercer University, then Union University, building a distinguished record of scholarship and service to the Baptist denomination.

Charles Bray Williams brought a spirit of religious revival to Howard, presided over record enrollments and admission to the Southern Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools, raised large sums of cash for the endowment and found majority support for a bold institutional vision. It simply wasn't enough, but Williams eventually won vindication for the most controversial aspect of his vision. Construction of Howard College's new campus began in 1953, the year after his death.

In the wake of this troubled period of war, caretaker presidents and bitter internal struggles, Howard turned to a man who knew the college, knew the presidency and, perhaps most important, enjoyed the support of the entire Howard community.

John C. Dawson

1921-1931

John C. Dawson was a native of Huntsville, Alabama, but lived there only a short time. His family relocated to Kentucky after his father died, the year after Dawson's birth. Dawson returned to Alabama as an educator, first in Scottsboro and, starting in 1903, at Howard College.

By 1921 Dawson had given notable service to Howard as a professor of modern languages, college dean and acting president. He also had taken significant leaves of absence--first to supervise the education of American troops in France and then to complete a doctoral degree at Columbia University.

Charles Bray Williams resigned abruptly in 1921, leaving hard feelings and ruptured relationships at the college. Needing first and foremost to heal the wounds of recent years and create a stable administration, Howard's trustees turned to the trusted and well-liked Dawson, who had received his Ph.D. the day after his predecessor's official resignation.

In return, Dawson provided a decade of stable leadership and steady institutional growth. But where Williams and J. M. Shelburne had worked toward big, bold visions of Howard's future, Dawson seems to have focused on progress by small increments.

One of Dawson's most innovative and farsighted policies allowed faculty to take leaves of absence, at half-pay, to complete doctorates and thus boost the college's reputation as they added value to their teaching. Dawson also presided over the addition of a science building, gymnasium, residence hall for women and a state-of-the-art athletic field; a surge in postwar enrollment (a 40 percent increase in 1921); a boom in academic societies; expansion of the Crimson; a first attempt at creating a pharmacy program; and creation of an academic journal dedicated to the scholarship of Howard faculty.

Dawson's longest-lived policy was his prohibition of dancing on the grounds that it was "not good for efficiency in class work" and because "the Baptists of Alabama are opposed to dancing." That policy, which survived for over 60 years, was part of a general crackdown (or revival, depending on one's perspective) at the college. Dawson also required students to memorize and recite a special Student's Prayer in convocation. And although Birmingham officially was considered a friend of the college, Dawson prohibited unnecessary visits. "A student who keeps continually running to town can be assured of a private interview," he warned.

Like most presidential wives before and since, Dawson's wife, Fletcher Stinson, was an active participant in the life of the college. In fact, she officially served as Howard's social director from 1921 until her death in 1927. Within a few years of her death John C. Dawson decided that almost three decades of service to the college, including a decade as president, was long enough.

A summer abroad in 1930 reminded the president of his love for teaching romance languages and literature. He announced his resignation that fall and departed from the office in February 1931 for an extended European tour before joining the faculty of the University of Alabama as head of the Department of Romance Languages. To the great surprise of the Howard community, the trip also served as a honeymoon for Dawson and Avis Marshall, Howard's recently-hired librarian.

Between 1921 and 1931, Howard increased enrollment by approximately 1,000 students and more than doubled its endowment, but also accumulated $100,000 in debt. As the Great Depression advanced, Dawson stepped aside in the hope that Howard would find a new president with the enthusiasm and ingenuity to save the college. Howard found such a president by the end of the decade, but not before suffering a bitter and chaotic period that brought charges of communist conspiracy at the college and an aggressive campaign by students, faculty and alumni to remove the president.

Thomas V. Neal

1932-1939

Thomas V. Neal accepted the presidency of Howard College at an especially precarious moment. The previous president, mindful of the deepening economic depression, recognized that Howard needed new ideas and expertise if it was to survive the crisis. Neal seemed the perfect match for that brief.

Born in west Georgia, Neal was raised on a farm and worked his way through school, serving as a laundry boy at Howard College to pay his tuition. After graduating from Howard in 1902 Neal attended seminary and spent over two decades in Texas as a pastor and educator. He had already proved his fundraising and institutional growth expertise as an administrator at Oklahoma Baptist University when Howard called him home to his Alma Mater.

Neal's first year as president was consumed by simply saving the college from the effects of the depression. He undertook extensive recruiting efforts and called a halt to construction of a multipurpose amphitheater he had inherited, recognizing that the college had more pressing uses for that money, material and energy. The faculty simply worked without pay during this period of crisis. By late 1933, Howard had reduced expenses enough that it was slowly emerging from its financial crisis.

Neal not only managed to save Howard, he actually expanded its curriculum and faculty and significantly improved its facilities. Federal aid increased enrollment and Neal even managed to raise faculty salaries. Not forgetting the students, he apparently declined to enforce the strict anti-dancing policies of his predecessor and built a new house for every Howard sorority.

Even in the darkest days of the depression, Neal kept faith in what Howard could become. "It is doubtful whether any college in the state or immediate region has weathered the economic storm as well as Howard," he said in 1934. Howard, he predicted, would soon enjoy an unprecedented "broadening and deepening of academic work."

Neal's optimism was justified. Howard seems to have been amazingly healthy by the middle of the decade, and in 1936 the Crimson proclaimed that, "happy days are here again." As evidence of this it offered, among other things, the observation that the faculty had bought more new cars in that year than in the entire previous decade.

By 1936 Howard had become the second largest college in the SBC system and even had some hope of soon being largely out of debt. Clearly, Neal had justified the trustee's faith in him to save the college. Yet only a few chaotic years later Neal would be forced out of office.

It seems that Neal's success also was his doom. He accrued to himself a great deal of power over college affairs, and although his decisions often served the college well, his unilateral decision-making alienated many students, faculty and alumni. Even some trustees feared to oppose Neal.

Tension over Neal's management style erupted into public view in 1938 when he clashed with the students over control of student activities fees. Threatened by increasing student dissent, Neal dug in, suspending some students who criticized the college. This brought conflict with a faculty that had sacrificed much to keep the college operating during the worst years of the depression.

When students called for the creation of a scholarship to benefit the president of the student body, with funds to be raised from student fees, Neal opposed the idea on the grounds that it was "opposed to the college's principles." Neal had recently fought to require ministerial students to pay tuition (after a tradition of full scholarships) and his opposition to the scholarship proposal pushed student opinion past the tipping point. Faculty allegedly urged students to "cut classes...and weave among the student body for a poll on student feeling." A student government committee concluded that Neal should resign.

A Howard professor temporarily calmed the students, but Neal pressed the issue by expelling the president of the student body. Faculty successfully intervened again, this time on behalf of the student. The immediate crisis had been averted, but the students soon voted to create the scholarship for the student body president, in spite of Neal's opposition. The students again called on Neal to resign, and alumni and faculty now joined the campaign, formally requesting that the trustees remove the president.

Neal responded to the increasing pressure by charging that communists were behind the movement against him. The trustees found no evidence of communist infiltration of the college, but nevertheless rejected the calls for Neal's resignation. Neal won the battle, but lost the war.

Recognizing that his position was untenable, Neal announced his resignation in January 1939. He finished the academic year and departed at the end of June, a few months after the president of Howard's alumni association claimed that Neal and a trustee had conspired to fire, on the pretext of cost savings, some of the faculty who had dared to oppose the president. To make matters worse, Howard's accreditation status was now in jeopardy. It was an unfortunate end for a president who had shepherded the college through the grave dangers of the depression.

Those dangers continued to threaten Howard and were compounded by another world war, but a veteran of war and state politics would lead the college through two decades of impressive growth and cultural change.

Harwell G. Davis

1939-1958

It seems especially fitting that in 1939 Harwell Goodwin "Major" Davis took on leadership of a college named for Christian prison reformer John Howard. As Alabama Attorney General earlier in the century, Davis helped expose and end the state's convict lease system, which amounted to a government-sponsored slave trade. In that service to the state, and in his service in combat during WWI, Davis had proven himself a gifted leader. After the cultural debacle of the Neal presidency, Davis must have seemed a safe and steadying figure. But who could have foreseen just how well he would lead Howard College through the dramatic changes to come?

Ironically, World War II, the greatest challenge Davis faced, made possible his two great accomplishments on behalf of Howard--helping the college thrive in wartime and relocate to a campus large enough to accommodate the tenacious, decades-old vision of a greater Howard.

Howard's fiscal health seemed to be steadily improving from the depths of the depression. With the considerable guidance of prominent businessman Frank Park Samford, newly-elected Chairman of the Board of Trustees, the college continued to chip away at its debt and maintain financial stability. The freshman class of 1940 was 10 percent larger than the previous year's, and a Howard centennial fundraising campaign aimed to eliminate all of Howard's debt and add campus facilities to accommodate the increasing number of students. But as the college prepared to celebrate its founding, war once again threatened its survival. Even before the U.S. entered the war against the Axis, enrollment slumped and some faculty departed for military service.

How could the college survive with its young men and faculty at war? Davis answered that question not by trying to remove the college from the path of the mobilizing national war machine, but by making the college a valuable part of its mechanism. First, Howard agreed to host a Civilian Pilot Training Program whose cadets would study alongside the college's other students. A Navy Air Corp program followed soon after and in 1943 the Navy awarded Howard a contract to host one of its large V-12 training programs. This brought the college the money and male students it needed to survive.

In fact, the college thrived. So valuable was the V-12 contract that in 1944 Howard enjoyed its best fiscal health in a decade. By 1945, Howard was out of debt, thanks not only to the V-12 program but also to continued support from state Baptists. The Navy program ended in fall 1945, and although Howard had to return some of the V-12 funds, Davis set aside much of the remaining wartime windfall in the hope that it would allow Howard to relocate.

Relocation of Howard College from East Lake had been discussed openly almost since the college relocated from Marion in 1887. Although advocacy for relocation had typically run afoul of alumni, it was clear by the 1940's that Howard must either have more room to grow or simply stop growing. The problems of the East Lake campus became even more acute as Howard reaped the rewards of the GI Bill, which gave returning veterans the opportunity to continue disrupted educations or afford education that would otherwise have been beyond their reach, financially.

In early 1947 Howard made official overtures for land in Birmingham's Lane Park and Roebuck communities, but by the summer they had purchased 225 acres on Lakeshore Drive. The idea was to not only relocate Howard to the new site, but also to relocate and incorporate Judson College as well. Little could be done to derail Howard's relocation, but opposition to relocating Judson prevented the creation of a Judson-Howard College.

Although the GI Bill effect declined by the early 1950's and war again unsettled the college, Howard pressed ahead with relocation to Lakeshore Drive. Only a handful of its planned facilities were complete at the time of the move in 1957, but the college's distinctive architectural unity was already evident. Davis rejected advice to select modern designs for the buildings, preferring instead the Georgian-Colonial style that became a key attraction of the new campus.

Davis saw the college through its first year on the new campus, then stepped aside. He had saved the college during wartime, given it the means to reach its full potential and expanded its academic programs without abandoning its distinctive cultural mission. For these reasons his presidency, the longest to that date, was the only one to leave an impression of completion, even though the new campus was mostly incomplete. To realize Davis' full vision for the campus, Howard turned to Leslie S. Wright.

Leslie Stephen Wright

1958-1983

Howard College president Harwell Goodwin Davis led the college through its second major relocation, then stepped down in 1958 after almost two decades of service. The Georgian-Colonial campus he envisioned would soon appear, but for the moment it was a sea of mud and a handful of buildings. The new president, Leslie S. Wright, would help realize Davis' vision, lead the way to university status and oversee the most significant cultural change since the college became coeducational.

Wright, a Birmingham native, completed his education in Kentucky before returning to Alabama as a teacher and coach before WWII. After serving as a U.S. Navy intelligence officer in the South Pacific, Wright worked for the federal government and eventually served as an assistant to U.S. Senator Lister Hill. At the time Wright was called to Howard, he had served the Baptist Foundation of Alabama for several years.

As a private segregated institution, Samford University was to some degree insulated from the events that defined Birmingham and the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950's and early 1960's. But a growing core of Samford faculty and students opposed segregation, and by the late 1960's changing laws made racist policies untenable even for private universities.

Wright resisted integration, but Samford's whites-only policy threatened federal student aid and institutional accreditation. Cumberland School of Law, facing the greatest immediate jeopardy, finally admitted Samford's first black student, Audrey Lattimore Gaston, in 1967. Once that door was opened at Cumberland, Wright was unable to close it there or prevent the integration of the university as a whole.

Although the desegregation of Samford proceeded peacefully, Wright often battled faculty and students over other university policies and the extent of presidential powers. In spite of this internal strife, Wright still managed to serve Samford longer than any president before or since. He also served as University Chancellor from his retirement in 1983 until his death in 1997.

In his 25 years as president, Leslie S. Wright helped realize the decades-old vision of a "greater Howard." His successor, Thomas E. Corts, continued on the same course, nurturing an ever-expanding campus and academic program largely made possible by the gifts of the Beeson family.

Thomas E. Corts

1983-2006

Born in Terre Haute, Indiana, and reared in Ashtabula, Ohio, Corts was one of seven siblings and the oldest brother to answer a calling other than full-time ministry. Although in his youth he was so involved in church activities that high school classmates jokingly called him "Reverend," Tom Corts did not dream of a career in the pulpit. In fact, he was more excited by the prospect of a career in journalism. Working for the local newspaper as a teenager, Corts reported on Friday night football games, mixing with players and coaches on the sidelines but never guessing that someday he would have ultimate responsibility of entire college athletic programs.

It was not until attending Georgetown College that Corts began to glimpse how he might combine his faith, his love for education and his family's tradition of service. With the guidance and interest of Georgetown President Robert L. Mills, Corts found an aptitude for and interest in the behind-the-scenes work of higher education. After graduating from Georgetown, Corts earned M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from Indiana University and served as executive vice president at Georgetown College before becoming president of Wingate College in 1974.

After becoming president of Samford University in 1983, Corts led the most dramatic period of growth in the university’s history. Samford now ranks among the South’s top five regional universities, regularly posts record enrollments, offers extensive international study experience and enjoys a growing reputation for innovative teaching and undergraduate research. Corts also led many major building projects and nurtured an endowment of over $200 million.

In addition to his presidency of Samford, Corts served as chairman of the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS), president of SACS, president of the American Association of Presidents of Independent Colleges and Universities and president of Alabama Citizens for Constitutional Reform.

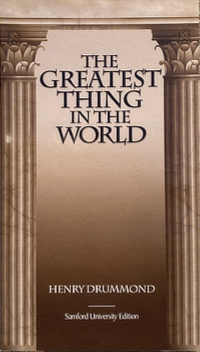

In 2003, Samford University produced a special edition of The Greatest Thing in the World by Henry Drummond which includes an introductory essay by Thomas E. and Marla Haas Corts. To reserve your copy, please email suadvancement@samford.edu.

In 2003, Samford University produced a special edition of The Greatest Thing in the World by Henry Drummond which includes an introductory essay by Thomas E. and Marla Haas Corts. To reserve your copy, please email suadvancement@samford.edu.

Andrew Westmoreland

2006-2021

Dr. Andrew Westmoreland led the university to embrace a vision to enrich and expand its service to students and further inspire their desire to meet the needs of the world. To advance this vision the university committed to a challenging strategic plan with four priorities: emphasize student success, enhance our community, extend our reach, and ensure financial strength. Forever Samford, a six-year, $300 million capital campaign launched to support the plan, is the largest undertaking of its kind in Samford University’s 179-year history. Funding from the campaign will help to ensure that Samford continues to prepare and send dedicated, thoughtful and ethical people out into the world.

Prior to his selection as president by the Samford Board of Trustees, he served eight years as president of Ouachita Baptist University, and, prior to that, on the administrative staff for more than 19 years in various capacities, including vice president for development and executive vice president.

Westmoreland is a graduate of Ouachita, having received a bachelor's degree in political science in 1979. He earned a master's degree in political science from the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, and a doctorate in higher education administration from the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. A native of the Batesville, Arkansas, area, he graduated from Batesville High School in 1975. He is married to Dr. Jeanna Westmoreland, who served as professor of education and dean of Ouachita's School of Education. The Westmorelands have one daughter, Riley, a graduate of Samford.

Beck A. Taylor

2021-Present

Beck A. Taylor came to Samford University after serving as the 18th president of Whitworth University in Spokane, Washington, since 2010. Prior to this appointment, Taylor served as dean and professor of economics for Samford’s Brock School of Business (2005-2010), and associate dean for research and faculty development for Baylor University’s Hankamer School of Business (1997-2005).

Taylor's tenure at Whitworth was highlighted by a renewed emphasis on community involvement; efforts to enhance academic programs and quality; the building of new campus infrastructure to facilitate the university's academic, athletic, and student life programs; the creation of newly endowed faculty positions and centers; leading Whitworth's largest-ever comprehensive fundraising campaign; and an emphasis on overall institutional effectiveness.

After earning his undergraduate degree from Baylor with majors in economics and finance, Taylor was employed as an analyst for Andersen Consulting (now Accenture) in Houston, Texas. He went on to earn his M.S. and Ph.D. in economics from Purdue University. After returning to the Baylor faculty, Taylor was named the first holder of the W.H. Smith Professorship in Economics. In 2002, he was appointed as a visiting scholar by Harvard University where he spent one year in residence at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

As dean of Samford's Brock School of Business, Taylor led the rapid transformation of the business school, including its renaming to honor Harry B. Brock, Jr., founder of Compass Bank. Taylor led the Brock School of Business to establish eight new academic programs, as well as the school's new honors program. The school's entrepreneurship program was recognized in 2010 as the nation's top emerging program by the U.S. Association for Small Business & Entrepreneurship. In an effort to build bridges between students and the Birmingham business community, Taylor established the Samford Business Network, as well as a 45-member advisory board of the region’s top business leaders.

Samford University Presidents

- Samuel Sterling Sherman

- Henry Talbird

- Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry

Edward Quinn Thornton - Samuel R. Freeman

- James T. Murfee

- Benjamin Franklin Riley

- A. W. McGaha

- A. D. Smith

- Frank M. Roof

- Andrew P. Montague

- James M. Shelburne

- Charles B. Williams

- John C. Dawson

- Thomas V. Neal

- Harwell G. Davis

- Leslie Stephen Wright

- Thomas E. Corts

- Andrew Westmoreland

- Beck A. Taylor