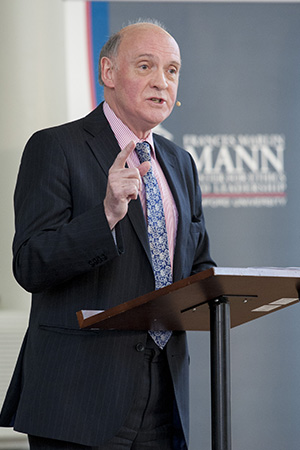

President Abraham Lincoln first read his proposed Emancipation Proclamation to his Cabinet July 22, 1862, but it was a full two months before he issued the historic document publicly, Lincoln scholar Richard Carwardine (left) said at Samford University Feb. 19.

One reason for the delay was the poor progress of the Civil War, Dr. Carwardine noted. "(Secretary of State William) Seward urged waiting for a military victory," he said, but the news from the battlefield continued to be bad as "(Confederate General Robert E.) Lee invaded Maryland."

It was not until Sept. 23 that Lincoln made the proclamation public, after the Battle of Antietam Sept. 17. Antietam was "no great Union triumph, but it was enough of a success to drive Lee out of Maryland and let Lincoln act," Carwardine said in his award-winning book, Lincoln: A Life of Purpose and Power. The proclamation stated that, on Jan. 1, 1863, all people held as slaves in those parts of the Union still in rebellion "shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free."

Carwardine, an American history specialist and president of Corpus Christi College at the University of Oxford, U.K., delivered Samford's Andrew Gerow Hodges Lecture on Ethics and Leadership, speaking to about 700 students and others in Reid Chapel. His book won the 2004 Lincoln Prize for the best book on the Civil War.

During the two-month delay, Lincoln bought time with his public answer to New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, who on Aug. 19 accused the President of "disdain of twenty million freedom-loving Unionists and of pampering the border states."

In a response to Greeley in the Washington Chronicle, Lincoln said, "My paramount objective in this struggle is to save the union, and it is not either to save or destroy slavery." Lincoln added, "If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it."

In closing his letter to Greeley, he said, "I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men every where could be free."

Carwardine called it "an adroit answer" because it reassured radicals that Lincoln was preparing for a dramatic step and conservatives that he had no such intention. But the historian said there was no misunderstanding of where Lincoln stood personally because he had built his reputation during the 1850s on his "earnest opposition to slavery." He quoted Lincoln as saying, "If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong."

The historian noted that the 2012 movie Lincoln showed that the President "used all his wiles to gain emancipation," portraying him as a "shrewd party operative."

During a panel discussion Feb. 18, Carwardine described Lincoln as "profoundly moral," "driven by injustice" and a man with "deep belief in natural rights." He said Lincoln believed "to deprive a slave of the fruits of his labor was an affront to justice."

The lecture and panel discussion were sponsored by Samford's Frances Marlin Mann Center for Ethics and Leadership. The Hodges lectureship is named for the Samford graduate and longtime trustee and supporter of the University.